Recreating UITextView - Custom Attributes

In the previous article we were solving the problem of displaying large volumes of text in UITextView and came up with reconstructing it in the face of TextCanvasView that knows how to handle text as we need it.

Today we will continue to play with the capabilities of UITextView and look at how to teach TextCanvasView to handle URL links and see how this can be extended to cover other scenarios.

Default Solution for Link Detection

To enable UITextView to recognise links, we need to include the .link option in its dataDetectorTypes property. It’s important that the isUserInteractionEnabled property of the view is set to true. Without it, UITextView will not process the links.

let view = UITextView()

view.dataDetectorTypes = [.link]Let’s Get Started

Recall that NSTextStorage is responsible for managing and storing text and its attributes. To modify the handling of attributes, we need to subclass it. We’ll name our new subclass TextCanvasStorage.

A key aspect of inheriting from NSTextStorage is taking control of text and its attributes storage. This is achieved by declaring a NSMutableAttributedString property, which becomes the hub for all text processing activities.

Moreover, the subclass must implement several methods from the parent:

string- a computed property that returns aStringinstance, representing the text to be displayedattributes(at:effectiveRange:)- returns the attributes of the text within a specified rangereplaceCharacters(in:with:)- replaces a substring with the given value within a specified rangesetAttributes(_:range:)- sets the specified attributes within a given range

final class TextCanvasStorage: NSTextStorage {

let backingStore = NSMutableAttributedString()

override var string: String {

backingStore.string

}

override func attributes(at location: Int, effectiveRange range: NSRangePointer?) -> [NSAttributedString.Key: Any] {

backingStore.attributes(at: location, effectiveRange: range)

}

override func replaceCharacters(in range: NSRange, with str: String) {

beginEditing()

backingStore.replaceCharacters(in: range, with: str)

edited(.editedCharacters, range: range, changeInLength: str.utf16.count - range.length)

endEditing()

}

override func setAttributes(_ attrs: [NSAttributedString.Key: Any]!, range: NSRange) {

beginEditing()

backingStore.setAttributes(attrs, range: range)

edited(.editedAttributes, range: range, changeInLength: 0)

endEditing()

}

}This code example illustrates the basic structure of TextCanvasStorage and the overriding of key methods that interact directly with backingStore—our internal storage.

The calls to beginEditing and endEditing allow the parent class to optimise and batch changes in the text content. The method edited(_:range:changeInLength:) notifies the system that the modifications have been completed.

Identifying Links

To highlight text as a link and enable the system to recognise it, we can use NSAttributedString.Key.link. This key will be applied within the processEditing method:

extension TextCanvasStorage {

override func processEditing() {

innerAttributedString.beginEditing()

let extendedRange = NSRange(location: .zero, length: string.count)

removeAttribute(.link, range: extendedRange)

string.urlRanges.forEach { url, range in

innerAttributedString.addAttributes([

.link: CanvasTapToken(value: url.absoluteString)

], range: range)

}

innerAttributedString.endEditing()

super.processEditing()

}

}In this code, we first remove all existing link attributes through a removeAttribute call to prevent duplication. Then, using the urlRanges array of ranges, we add the .link attribute to the corresponding text fragments.

💡 For more details on working with text attributes, you can read this article.

To find web link, you can use NSRegularExpression:

extension NSRegularExpression {

static let httpURL: NSRegularExpression = {

try! NSRegularExpression(pattern: "(?:https?:\\/\\/)?(?:www\\.)?[a-zA-Z0-9-]+\\.[a-zA-Z]{2,}(?:\\/[^\\s]*)?")

}()

}

extension String {

var urlRanges: [(URL, NSRange)] {

NSRegularExpression.httpURL.matches(

in: self,

options: [],

range: NSRange(

location: .zero,

length: utf16.count

)

)

.compactMap { match in

guard let range = Range(match.range, in: self) else { return nil }

if let url = URL(string: String(self[range])) {

return (url, match.range)

}

return nil

}

}

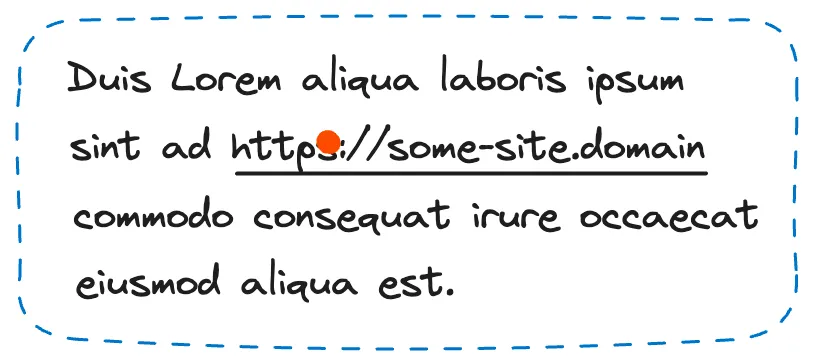

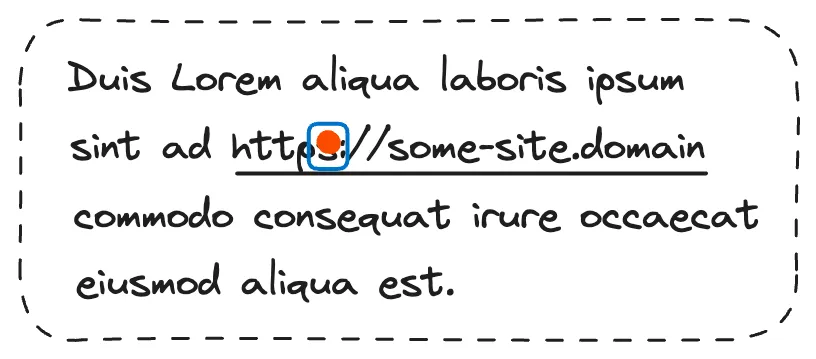

}At this stage, we already have a working implementation for highlighting links in the text, making our TextCanvasView even more functional. However, to make these links interactive, it’s necessary to add tap handling.

Interaction

TextCanvasView, by inheriting UIResponder, has the capability to handle user interactions, such as touches. To process taps on links, we override the method touchesEnded(_:with:), which allows us to determine whether a touch was made on an interactive element and, accordingly, respond to this action:

extension TextCanvasStorage {

override func touchesEnded(_ touches: Set<UITouch>, with event: UIEvent?) {

if let token = token(at: touches) {

onTokenTap?(token)

} else {

super.touchesEnded(touches, with: event)

}

}

}In this example, token(at:) is a function that determines whether the touch point corresponds to the range of a link. onTokenTap is a closure that is invoked if the touch was made on a link:

final class TextCanvasStorage {

...

var onTokenTap: ((URL) -> Void)?

}To determine which specific link was activated upon tapping in TextCanvasView, we start by obtaining the coordinates of the tap. This is done using UITouch and the method location(in:), which returns the point of touch within the coordinate system of our view.

After obtaining the coordinates, we proceed to work with NSLayoutManager, which plays an important role in converting the positions and sizes of glyphs in the text. Its method glyphIndex(for:in:) allows us to obtain the index of the character within whose bounds the tap was made.

Knowing the glyph index, we can determine if it corresponds to a link by referring to our TextCanvasStorage. For this, we request the .link attribute by the character index. If the link exists, we can perform the corresponding action, such as opening it in a browser.

The implementation of the described algorithm is presented below:

private extension TextCanvasView {

func token(at touches: Set<UITouch>) -> URL? {

guard

let container,

let location = touches.first?.location(in: self),

storage.length > .zero

else { return nil }

let glyphIndex = layout.glyphIndex(for: location, in: container)

guard

glyphIndex >= .zero,

glyphIndex != NSNotFound,

glyphIndex < storage.length

else { return nil }

return storage.attribute(

.link,

at: glyphIndex,

longestEffectiveRange: nil,

in: NSRange(location: .zero, length: storage.length)

) as? URL

}

}Now, the only thing left to do is to add calls to UIApplication so that the user can navigate to the link by opening it in a browser.

view.onTokenTap { url in

let application = UIApplication.shared

if application.canOpenURL(url) {

application.open(url)

}

}

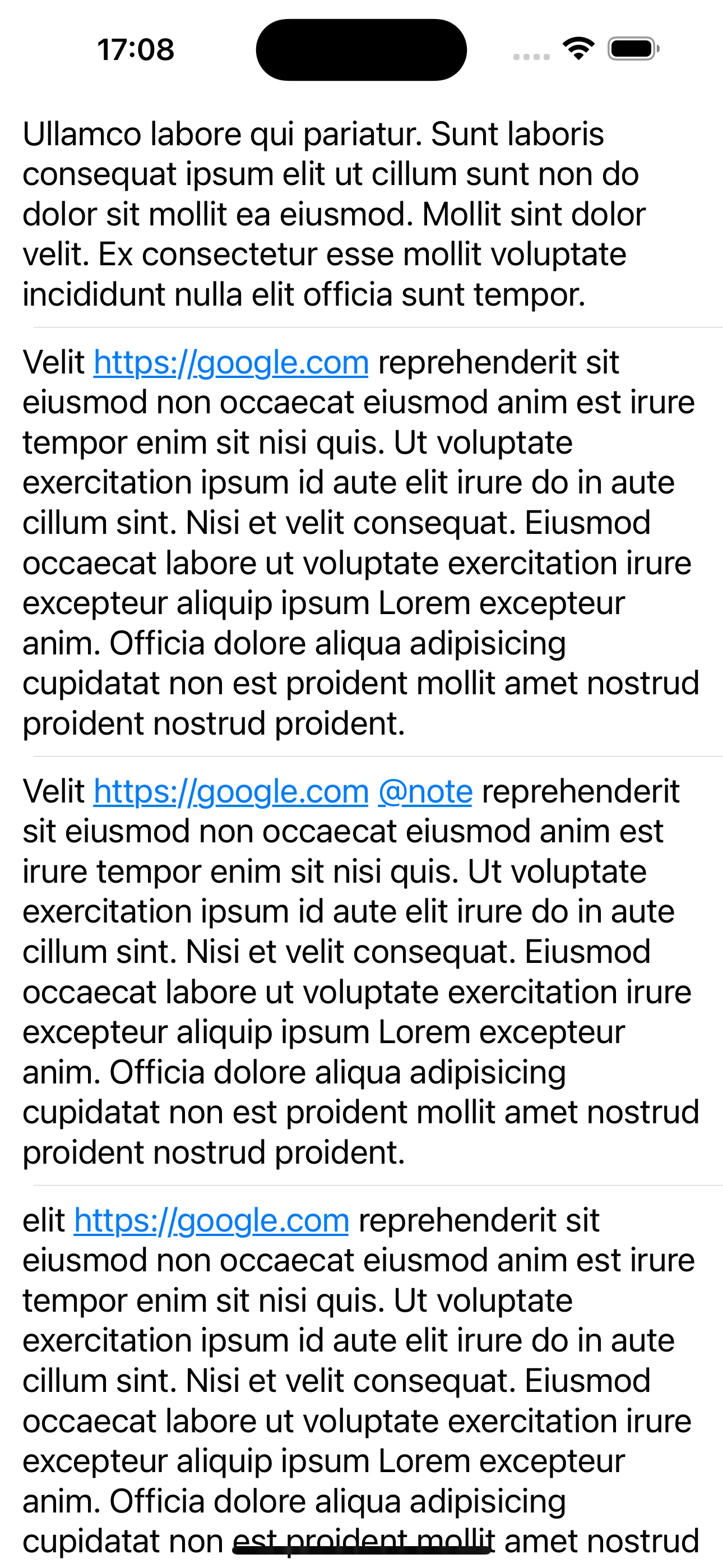

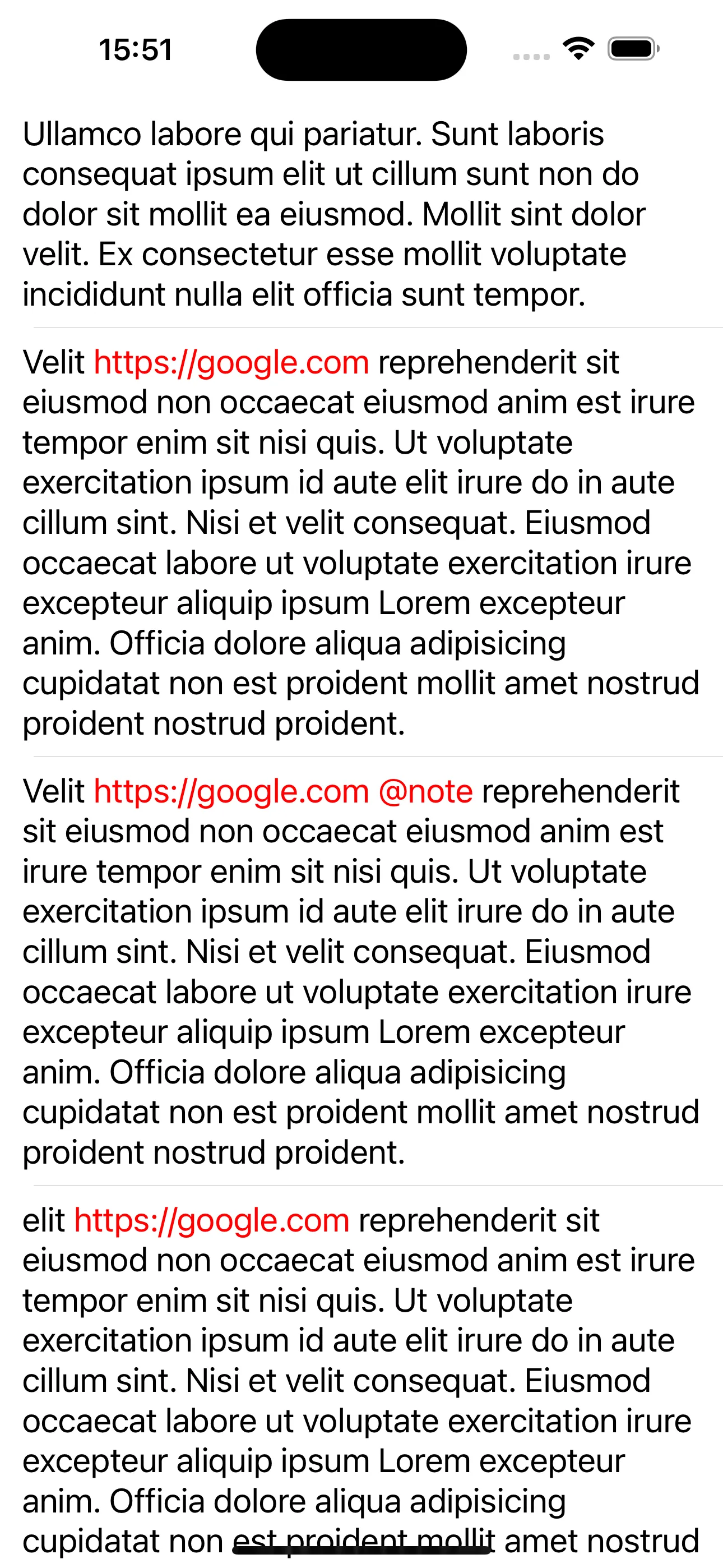

Expanding Capabilities

To extend the functionality of TextCanvasView beyond handling standard web links, we can add support for other types of interactive elements, such as user mentions marked by the “@” symbol.

In this case, our task is to expand the processEditing method by incorporating a mechanism to find and process such mentions:

extension TextCanvasStorage {

override func processEditing() {

...

string.mentionsRanges.forEach { (mention, range) in

innerAttributedString.addAttributes([

.link: mention

], range: range)

}

...

}

}The implementation of the search could look like this. Here, instead of returning a URL instance, a String is returned, which differs from how links are handled, and I’ll explain more about this distinction moving forward.

extension NSRegularExpression {

static let mention: NSRegularExpression = {

try! NSRegularExpression(pattern: "@[a-zA-Z]+")

}()

}

extension String {

var mentionsRanges: [(String, NSRange)] {

NSRegularExpression.mention.matches(

in: self,

options: [],

range: NSRange(

location: .zero,

length: utf16.count

)

)

.compactMap { match in

guard let range = Range(match.range, in: self) else { return nil }

return (String(self[range]), match.range)

}

}

}

To ensure uniform handling of both links and mentions, we declare a nested enumeration Token within TextCanvasView. This enumeration includes cases for handling both strings and URLs, allowing us to unify the processing logic and make the code more organised and understandable:

final class TextCanvasView {

enum Token {

case url(URL)

case string(String)

}

...

}During text processing in processEditing, detected mentions and links will now be wrapped in the corresponding values of the Token enumeration:

extension TextCanvasStorage {

override func processEditing() {

...

string.urlRanges.forEach { url, range in

innerAttributedString.addAttributes([

.link: TextCanvasView.Token.url(url)

], range: range)

}

string.mentionsRanges.forEach { (mention, range) in

innerAttributedString.addAttributes([

.link: TextCanvasView.Token.string(mention)

], range: range)

}

...

}

}The token(at:) method will return a Token instead of a URL:

private extension TextCanvasView {

func token(at touches: Set<UITouch>) -> Token? {

...

return storage.attribute(

.link,

at: glyphIndex,

longestEffectiveRange: nil,

in: NSRange(location: .zero, length: storage.length)

) as? Token

}

}And onTokenTap will now provide an instance of Token:

final class TextCanvasStorage {

...

var onTokenTap: ((Token) -> Void)?

}And the call to the handler might look something like this:

view.onTokenTap { token in

switch token {

case let .url(url):

let application = UIApplication.shared

if application.canOpenURL(url) {

application.open(url)

}

case let .string(string):

print(string)

}

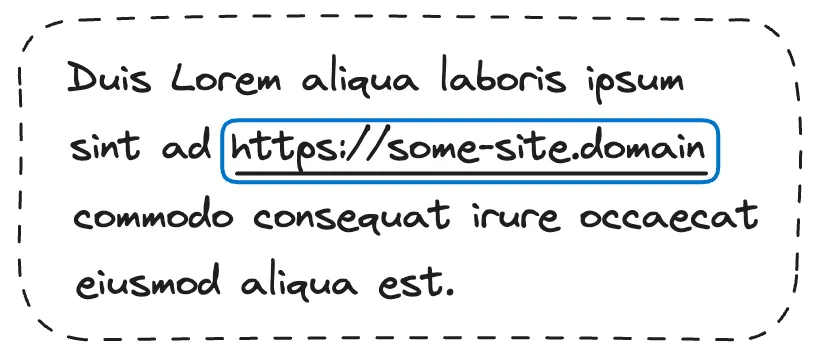

}We can also customise the appearance of text elements using attributes. Previously, we mentioned that the .link attribute defines the colour and underlining for substrings. To introduce a custom attribute, it’s necessary to define a new key:

private extension NSAttributedString.Key {

static let token = NSAttributedString.Key("TextCanvasView_token")

}In processEditing, instead of .link, we use the new key along with the necessary attributes that define the text’s appearance:

extension TextCanvasStorage {

override func processEditing() {

...

string.urlRanges.forEach { url, range in

innerAttributedString.addAttributes([

.token: TextCanvasView.Token.url(url),

.foregroundColor: UIColor.red

], range: range)

}

string.mentionsRanges.forEach { (mention, range) in

innerAttributedString.addAttributes([

.token: TextCanvasView.Token.string(mention),

.foregroundColor: UIColor.red

], range: range)

}

...

}

}Also, in token(at:), we replace .link with the newly declared key:

private extension TextCanvasView {

func token(at touches: Set<UITouch>) -> Token? {

...

return storage.attribute(

.token,

at: glyphIndex,

longestEffectiveRange: nil,

in: NSRange(location: .zero, length: storage.length)

) as? Token

}

}

Conclusion

We’ve enabled TextCanvasView to handle interactive elements such as links and mentions. This defines the way for further customisation and expanding capabilities in processing specific user interaction scenarios with text.

In the next article, we will continue to explore the possibilities of working with text elements and add contextual interaction to our view. See you then!